A Civics Education for Privacy

The Mozilla advocacy and campaign teams are meeting this week to plan a multi-year “privacy, security, surveillance” campaign. We’re searching for an issue where we can make a real impact.

I am pushing for “security” to be tip of our campaign’s spear. Something like “we want to know that our devices, communications, and Internet/web services are secure against compromises and attacks from governments or criminals. We don’t want them to contain any deliberate or known weaknesses or backdoors.” This is the kind of principle that resonates across ideological divides, gets people nodding their heads at the watercooler, and gets the red-meat internet people fired up about backdoors in Microsoft products. No public figure wants to be on record saying “a vulnerable Internet is a good thing.”

Intelligence and defense are pouring enormous resources into making the internet communications of our adversaries more vulnerable, which makes everyone more vulnerable. It’s counterproductive. It’s why Yochai Benkler talks in terms of an autoimmune disease; “the defense system attacking the body politic.” This problem is illustrated in ongoing leaks that suggest agencies are looking to deploy malware at mass scale. “When they deploy malware on systems,” security researcher Mikko Hypponen says, “they potentially create new vulnerabilities in these systems, making them more vulnerable for attacks by third parties.”

This is why I think we should put our energy behind “securing the internet.” We can’t stop spying, but we can affect a state change in internet security.

“How to Act”

But even in a perfectly secure internet, users’ behavior leaves them vulnerable to any number of privacy harms. “Privacy” is not the kind of value that gets codified in software; it takes user awareness and action. So our campaign must be centered on educating users about specific actions they can take to address the problem.

“Privacy” is a collective problem. We need to be the change we want to see.

We need to teach people how to act in an information society. We need young people to understand this part of “citizenship” on the web; how even seemingly passive usage of the web forms a profile, a trail, an exposure.

A “privacy civics” education should be part of every high school curriculum—like home economics or traditional civics.

Mozilla is developing a Web Literacy Map and associated curriculum. Privacy will be the toughest part of this map to teach, because it’s unbelievably abstract. When “Connecting,” for instance, a web literate person should have competencies like:

“Managing the digital footprint of an online persona.”

“Identifying and taking steps to keep important elements of identity private.”

But “digital footprint” “user persona” and even “privacy” are abstractions. To introduce these abstractions, you need stories and metaphors to explain these concepts, to build on the understanding, and ultimately form a consciousness and an understanding of the user’s privacy context in the wider web. For example, we might explain the exposure that a user gets from metadata because “it’s like having a guy parked outside your house with binoculars. He might not know exactly what’s happening inside, but he can take notes and find patterns.”

It’s not hard to imagine worksheets or 2001 era CD-ROMS to use these stories address these competencies. But this is 2014, and we can do way better. We should be able to make this kind of thing less abstract, more tangible, using the web.

A Mozilla-Style Privacy Education? Lessons from MozFest 2013

What does a Mozilla-style privacy education look like? What should it feel like?

Clearly, it should be hands-on, interactive, instructive. We couldn’t teach this stuff in a boring way. When we teach HTML, we invite kids to hack webpages or remix hip-hop videos. Maybe when we teach privacy/security workshops, we should invite kids to be an NSA analyst on their own metadata? Or to perform a man-in-the-middle attack or tailor advertisements to their peers?

I don’t know for sure, but I do know that a Mozilla privacy education should be much cooler than reading a book.

MozFest is a great place to test hypotheses, work with communities, and intuit where we ought to be going. We use MozFest to learn from the open web communities and get smarter.

The 2013 Festival featured a track on privacy and user data. I helped organize with Alex Fowler and Alina Hua. We called it “Look Who’s Watching,” in a nod to the Stop Watching Us coalition. “Look Who’s Watching” suggests an educational complement to that activist project. Internet users should look around, undergo a process of discovery, and better understand how they expose themselves when they use the web. To understand who’s watching your online movements is an essential part of being an informed, empowered user.

The Privacy Track at MozFest 2013 was billed as an opportunity to “shape a full response to modern privacy problems.” These problems include but are not limited to behavioral targeting, information leakage, data correlation and generic attacks to privacy, location and mobility tracking, profiling and data mining, surveillance, and good old fashioned oversharing.

Lots of privacy educators showed up with their own theories of change. Each has strengths, weaknesses, and pedagogical baggage. Let’s take stock of a few:

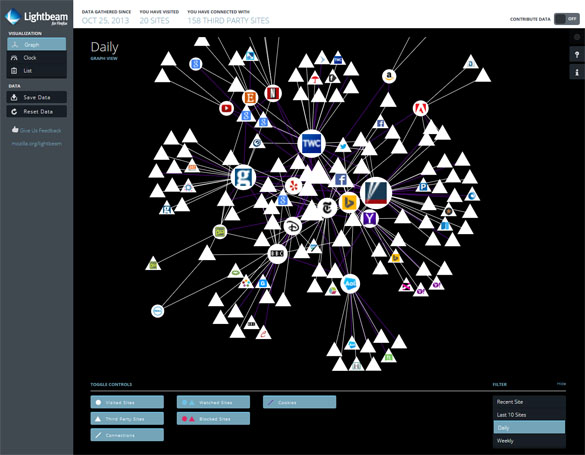

Lightbeam?

Lightbeam shows how third-party cookies enable a web of tracking

The highest profile public education initiative that Mozilla has done to date is Lightbeam, in collaboration with the Ford Foundation.

Lightbeam is a Firefox add-on that visualizes how you’re affected by third-party commercial tracking. As you browse, Lightbeam reveals how third-party cookies paint a picture of your online activity, and how that’s not transparent to the average user.

We have billed this as being explicitly educational, but we don’t yet have a theory of how Lightbeam should be presented in workshop setting. Getting Lightbeam workshops in place throughout the Webmaker network is seriously low-hanging fruit.

However, Lightbeam is sort of stuck in time, and will cease being valuable when the ad titans move away from cookies and toward fingerprinting. It’s overly mechanical. More importantly, it doesn’t get to the deeper problems implied by this knowledge graph falling into the wrong hands.

Don’t get me wrong—I’m a huge fan of Lightbeam. It’s individualized and interactive, and illustrates a specific problem. But it’s not yet the kind of integrated, interactive, innovative privacy education that we need.

Trace My Data Shadow?

Me and My Shadow offers a way to measure the invisible and abstract

The more latent, scary stuff is hard to measure (or explain). At MozFest, we were fortunate to have Becky Kazansky representing Tactical Tech, who have created resources like “Security-in-a-Box” and “Me and My Shadow.”

Me and My Shadow is a well-designed curriculum that gets to the meatiest problems in privacy: how your data shadow can be used against you.

A lot of people conflate the loss of privacy with oversharing on social networks. But smart people know the problem is not what you purposefully put into social media—it’s the data trail that you (unavoidably) generate as a web user. MyShadow.org includes a set of tools to measure your data shadow. Once you’ve measured your shadow, it points to ways to “explore your traces,” “resize your shadow,” and ultimately “turn the tables.”

Shadow Tracers Kit

“Teaching privacy” involves helping people develop a mental model of mechanics of the web. Understand exposure and trust. Develop transactional intelligence about their data. In a perfect world this would be about leveling everyone up, informing a smarter conversation and smarter usage at all levels—ultimately reaching policymakers. My Shadow is getting a little closer to the sweet spot, but it’s a little too fragmented. It’s not yet cohesive or well-integrated with a campaign. Maybe we can help.

Cryptoparties?

There's a cryptoparty in your neighborhood

CRYPTOPARTIES are about people understanding the consequences of their own behaviors and adjusting. Around the world, small groups of people attend teach-ins where they learn skills in small groups: PGP encryption, Tor anonymous browsing, OTR secure communications. To me it seems a little hard to make this mainstream—though Cory Doctorow probably has ideas about how to make this cool. The bigger problem is that anonymization is not necessarily the change we want to see—it sets up a frame where there are privacy-haves who justifiably wear tin foil hats, and privacy-have-nots who think that they’re weird.

But there’s a big opportunity to more systematically bring privacy teaching, learning and crypto-parties into the Webmaker network.

Privacy Drama?

Take This Lollipop makes it personal

Privacy drama is about take invisible, abstract problems and make them immediate in personalized narratives. You could imagine a documentary that uses your data and APIs to demonstrate how you would be subject to price discrimination, for instance. We brainstormed a list at MozFest, and there are interactive proofs-of-concept, like Take This Lollipop (which spins a privacy scare narrative from your Facebook data) and the privacy documentary side-project of Mozilla’s own Brett Gaylor.

I’ll be expanding on some of these ideas in a talk to the Tribeca Film Institute in April. Will do a post later on.

Hands-on computer science education?

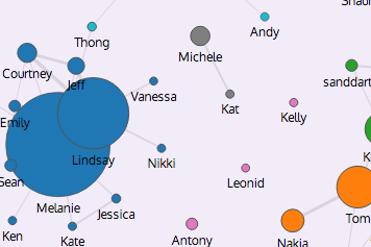

Immersion will enable you to analyze your email metadata, the way an NSA analyst would

Another approach suggests that the best way to understand security vulnerabilities is to “do it yourself,” having a visceral hands-on experience.

At MozFest, we had a session that taught participants to use Wireshark to perform a man-in-the-middle attack on their own mobile phones. Participants learned this basic interception technique to reveal how the mobile apps they use are ‘phoning home’ — enabling mobile tracking without consent. But after performing this exercise, participants should understand the risks of having their traffic intercepted, and will probably want to see that HTTPS is active before ever typing a password.

Another team from MIT (the Immersion project) set out to explode the myth that user metadata is “just metadata”:

What can someone learn from what you write on your “virtual envelopes”? After an introduction to the MIT Immersion tool, you’ll perform a metadata analysis of your own inbox. Participants will gain insights about surveillance of metadata through some simple coding exercises (Python) if you have Gmail, try Immersion here.

After performing a metadata analysis of your own inbox, a facilitator can ask leading questions like: “Is that female with whom you communicated the most in 2012 your girlfriend? I see you didn’t communicate at all in 2013—did you break up?” Having a personal experience like this will show that patterns and content can be inferred from metadata, and that such power can be exploited by advertisers and law enforcement.

What now?

On display are varying pedagogical theories. They can all co-exist. But how should Mozilla concentrate efforts?

I am convinced that we need an answer, and to lead a “privacy civics education” for the world.

No Mozilla campaign would be complete without mobilizing users to take direct action on this very collective problem.

About this entry

You’re currently reading “A Civics Education for Privacy,” an entry on Ben's blog.

- Published:

- 3.17.14 / 9pm

- Category:

- Drumbeat, Filmmaking, Innovation, Learning, Mozilla, Strategy, Talks, Web Makers

- Tags:

Comments are closed

Comments are currently closed on this entry.